There are two important questions to ask about Charles Babbage, why did he fail to build his mechanical computers? And what can his failures teach computer scientists and businesses today? One of the reasons Babbage failed is because of his difficult, unstable personality. The breakdown of his relationship with his chief engineer, Joseph Clement, on the Difference Engine project is a well-documented example.

There are other important reasons he failed and these are linked to his ambitions and the complexity of the projects he undertook. Babbage can be described as ambitious, arrogant and resentful. He was despondent when his ambitions were not met and he didn’t receive the accolades he expected, as he wrote later in life.

When driven by exhausted means and injured health almost to despair of the achievement of his life’s great object — when the brain itself reels beneath the weight its own ambition has imposed, and the world’s neglect aggravates the throbbings of an overtasked frame.

…

The certainty that a future age will repair the injustice of the present, and the knowledge that the more distant the day of reparation, the more he has outstripped the efforts of his contemporaries, may well sustain him against the sneers of the ignorant, or the jealousy of rivals.

Babbage was convinced of his own brilliance despite failing to deliver a working and useful mechanical computer. He seemed determined to build a grand, mechanical computer of great complexity. A machine which would prove his genius and result in many honours and privileges.

Long since the 19th-century computer scientists have learnt valuable lessons about ambition and complexity, and how they can destroy projects. Generally, those who are too ambitious and overcomplicate things tend to fail, sometimes with terrible consequences.

One of the most important concepts in problem-solving is “satisficing” which was defined by the political scientist Herbert Simon. In very basic terms satisficing means searching for an acceptable solution when no optimal solution exists. The software developer and educator Robert L Glass describes Herbert Simon’s concept of satisficing as follows.

He [Simon] means a solution that works, one that is “good enough,” one that stops short of being an optimizing solution but will do the job in question.

Glass in his book Software Creativity extends this idea to the BIEGE principle, “Better is the Enemy of Good Enough”.

If you have a problem for which a satisficing solution will do, don’t keep working the problem trying to find the optimizing one.

What Glass means is that optimising or seeking perfection can easily become a time and money sink that leads to failure. It is wise therefore to avoid complexity and overambition as they often block the delivery of ‘business value’.

From a business perspective, it’s better to deliver a good enough solution than spend extra time gold-plating something. The reasons should be obvious, the quicker you release something the faster you receive feedback. This helps you discover the viability of a product and make adjustments to improve it. If you lose time gold-plating a solution you may fail to deliver what the market wants or fail to deliver at all.

The question is, did Babbage fall foul of the Good Enough principle? Did he fail to deliver due to overambition and complexity? The honest answer is yes, and there is plenty of evidence to support this argument. Babbage’s computers aimed to more accurately and efficiently produce mathematical tables. This is what we might describe as the ‘value proposition’.

However, people at the time were not convinced by Babbage’s value proposition. The Astronomer Royal, George Airy, was one of the people sceptical of the value of the Difference Engines. As Doron Swade describes in his book about Babbage and his Difference Engines.

Airy was not alone in his less than absolute commitment to the utility of the Engines. Others raised questions about whether the high precision offered by the machines in working to twenty, forty, fifty and even one hundred figures of accuracy could be justified when practical measurements could be made to only three or four figures.

Why produce a machine of such complexity when it wasn’t required for the problem it set out to solve? Glass would probably describe this as a prime example of gold-plating.

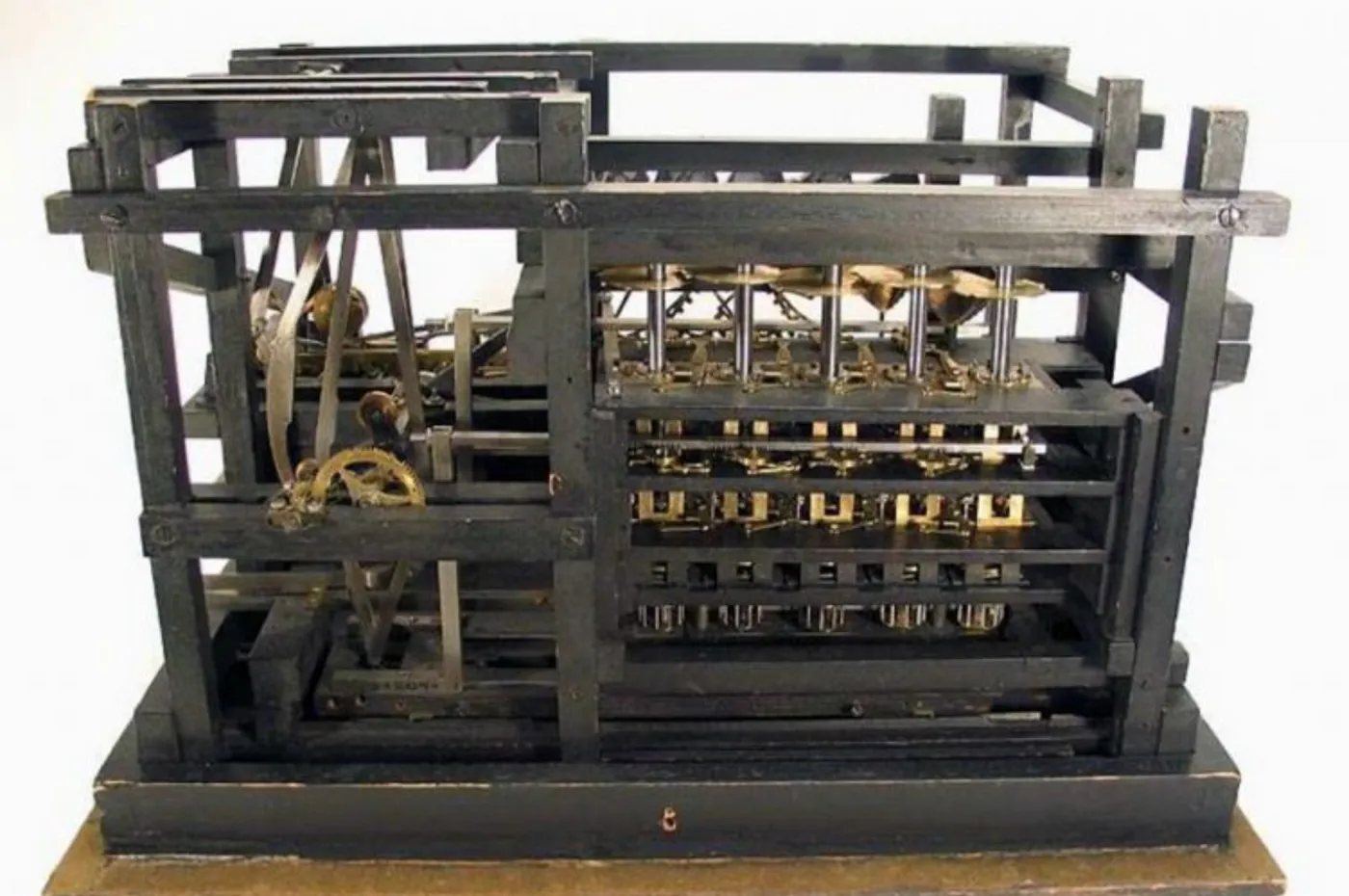

Babbage failed to deliver anything more than a few example pieces from his engine designs. In fact, it wasn’t until 1991 that the Science Museum built a working version of the Difference Engine No 2. Despite modern industrial practices and processes it still took them 6 years to complete the project, which should highlight the complexity involved.

In addition, several individuals around the time of Babbage built simpler Difference Engines or mechanical computers which actually worked. The most famous was built by Swedish father and son inventors Georg and Edvard Scheutz. Their Difference Engine was much simpler, working to only three orders of difference compared to Babbage’s proposal of six. The engine also had a functioning printing press which was critical for producing mathematical tables. Scheutz even managed to sell one of his engines.

The difference between the Scheutz and Babbage approach is described by Swade, and it provides more evidence that Babbage overcomplicated his engines.

Babbage had demanded the highest precision in the manufacture of parts for his Engine, and British technology, which was the most advanced anywhere, was stretched to its limits and beyond. Edvard’s machine has a rough wooden frame and was made using a simple lathe and hand tools by a young man with craft skills. A Swedish teenager had succeeded where the best of British had failed. The successful completion of the Swedish prototype raises questions about whether Babbage’s demand for the highest precision was warranted by the needs of the mechanisms.

Others also produced working mechanical engines or analogue computers. This included Johann Helfrich Von Müller during the 1780s, Martin Wiberg in 1859 and William Jevons in 1869. What links these mechanical analogue computers is none of them produced any real value beyond engineering novelty. In fact, both Georg and Edvard Scheutz ended their lives bankrupt, unable to create a business from their engines.

It wasn’t until the 1880s and 90s that Herman Hollerith achieved a real business breakthrough for computers with his electromechanical tabulating machines. His machines made census data processing much more efficient and their use expanded to other industries. Hollerith’s inventions and business would eventually help form the foundation of IBM.

It’s interesting to consider whether Babbage would have discovered the futility of mechanical computers if he’d been less ambitious and more efficient in his work. If he’d built simpler engines and tested his ideas faster would he have received the feedback required to pivot his work? We’ll never know, but he was a prolific inventor so he may have achieved far greater feats if he’d focused elsewhere. Then he may have received the accolades his ambition desired.

Computer scientists and businesses can learn a great deal from the story of Charles Babbage and his failure to deliver. Ambition is important but it shouldn’t cloud your judgement or be taken too far, never hold on to an idea or principle too tightly. Be realistic about what can be achieved by you or your business. Minimise complexity as it can result in failure, even if the idea is good, and always consider what the simplest step forward is. Test your ideas quickly, don’t waste time gold-plating an idea which isn’t proven. Ultimately it’s better to deliver a satisficing solution than nothing at all.

Sadly Charles Babbage failed to do any of this, and as Robert L Glass says.

One shouldn’t strive for perfection in a field where getting something that works is difficult enough.

Useful Resources: