How do you wish to be remembered? It is a question we all consider at some point in our lives. A more talented member of society may wish to be remembered as a brilliant mind like Charles Babbage. A man who today is regarded as the father of modern computing. Interestingly though, Charles Babbage wasn’t remembered as fondly at the time of his death as he is today.

I found some evidence for this when I recently remembered a wonderful resource for researching history, the British Newspaper Archive. I used it for my dissertation on the General Strike nearly 20 years ago. At the time you had to go to the archive in North London and look at the microfilm, now it’s all online. The archive provides a great primary source and insight on how the people of the day interpreted issues.

Out of interest, I decided to look up the death of Charles Babbage, to see if it surfaced anything of interest, I wasn’t disappointed. I discovered a memoir by the Daily Telegraph, written after his death and republished in the West Somerset Free Press. It wouldn’t have been pleasant reading for the great man. It portrays Babbage as a disappointed, sad and tragic figure.

To begin it makes light of his fame.

He moved as one not belonging to the spheres he joined, for his associates had all one by one departed; and those who are now rising to scientific fame knew him but little or knew him not at all. It may be said of him more truly than it has lately been of others that he had outlived his fame;

It highlights how by the end of Babbage’s life he’d become better known for his criticism of working-class social norms, including organ grinders.

It is … more desirable that the leading labours of his life should be briefly recorded, that he may be remembered as something higher than a mere crusader against peripatetic musicians.

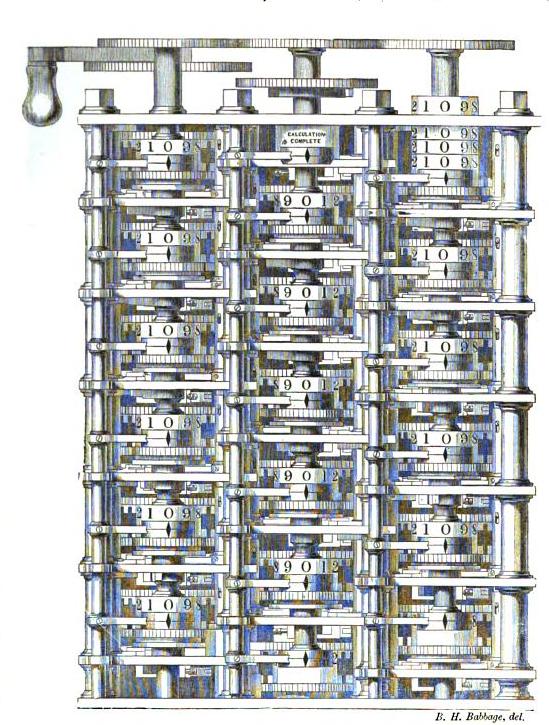

Babbage’s failure to finish his Difference Engine is described as a “sad tale of labour misspent.” And covers the “simple printer” from Sweden Georg Scheutz who successfully built a version of Babbage’s Difference Engine.

But this sad tale of labour misspent and hopes frustrated has a sequel that, if omitted, would render our brief memoir of Babbage incomplete. In 1834 or 1835, a simple printer in Stockholm, M. Scheutz, learnt through Dr. Lardner’s article in the Edinburgh Review of the existence of the Difference Engine. He was fascinated by the idea of it, and was impelled to attempt a machine for the same purpose. He devised one, and, with the assistance of his son, overcame all the difficulties, technical and fiscal, of its construction. Like Babbage’s in principle, it calculated tables by differences and printed the results; but in details it was widely different, so different that it could not have been copied in any part from the British machine, and it fulfilled the full hopes of its inventor. Before us, as we write, lies a Table of Logarithms calculated and printed by it, and specimens of other trigonometrical and astronomical tables similarly produced. And the book containing them is dedicated to Charles Babbage. The Briton had sown and the Swede had reapéd.

The memoir does finish on a positive note for Babbage. Pointing out he held no animosity towards Mr Scheutz who achieved what he hadn’t. In fact, Babbage even celebrated the achievement.

And was the sower angered at the success of the reaper? By no means. At one of the meetings of the Royal Society, when a gold medal was being awarded to a foreign savant for a brilliant investigation, Babbage rose and soundly rated the society’s council for not voting that medal to Scheutz for his machine, which then stood in an adjoining room. This act does not savour of that “malignity” which Babbage’s enemies said he festered on account of the abandoment of his scheme by the Government.

The above is only a single source representing a single opinion. But for a prestigious publication like the Daily Telegraph to share these views suggests Babbage wasn’t lauded unreservedly by his contemporaries. It implies some or many of his peers pitied him by his death. We might even describe Babbage as the Van Gogh of computing, a brilliant but sad and tragic man who only found respect and admiration after death.

Useful Sources: